What makes a society an internet society?

/Is Botswana an internet society? Infrastructure is one thing, linking new media in viable ways to economic practices and people's everyday life is another.

The answer is yes – but then again; maybe not.

In Botswana, internet access and -use has exploded. Botswana has invested a formidable amount of its money on developing the internet infrastructure. It has a 150% SIM-card coverage, it has one of the highest percentages of internet subscribers on the African continent, it has the highest percentage of Facebook users on the sub-Saharan mainland, and it has a national policy of distributing internet signals and access points to the vast, thinly populated areas of the Kalahari (which covers the bulk of Botswana).

“Botswana has invested a formidable amount of its money on developing the internet infrastructure.”

However, it can hardly be said to be an internet society if we go beyond the selected figures and approach the question from the point of view of institutions and citizens. Does it play a key part in the national economy? And does it constitute a significant part of ordinary people’s lives?

Botswana is a middle income country, one of the richest in sub-Saharan Africa. It is well managed; free and fair elections, relatively little corruption, and although the difference between the rich and poor is huge the country has - in an African perspective - a well-developed social security system; old age pensions and various social welfare programs. Its economic success rests on two pillars; diamonds (and other minerals) and cattle.

The diamond industry is a global industry and therefore relies heavily on modern, internet-linked management systems. In this way some high-tech-related employment is trickling into the Botswana population. However, it is an industry which to a large extent is controlled by foreign capital (South Africa’s de Beers mining company being the major actor), thus the bulk of the Botswana work-force in this sector is typically manual labour, with little or no digital technological competence being required.

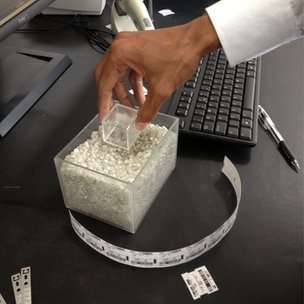

The cattle industry is a more diverse industry when it comes to ICT-use. On the one hand, a great deal of the nation’s animals is owned by ordinary Batswana. Cattle hold a special place in the Botswana culture; it is closely linked to ideas about a good life, and it is also important as a part of male identity. Thus, people (also women) who have some capital to spare will invest in cattle. This holds true also for urban people. All citizens have (most often close) relatives in rural areas and typically they place their cattle on some kin’s cattle posts (moraka) out in the veld. The extended family's role and the moraka as a site suggest that today's management of cattle is close to the ways they have always managed their life stock. However, looking closer at it one sees that new technologies have crept also into this form of life. The industry’s national economic significance has led to the state authorities’ intervening into the core of the practice. Problems such as sickness in the herds, as well as thefts, have prompted the state to introduced new ICTs as means of surveilling and monitoring the animal population. Now almost all Botswana cattle are RFID-tagged.

This is a system that uniquely identifies each and every animal by inserting a small tag inside the animal, tags that can be read by handheld devices which then load the information into large databases. In this way information about vaccination, breed, ownership and all other relevant information can be extracted in a split second. Effective management of Botswana stock is the result, helping to develop a viable cattle export industry.

And the ICT-based management is not confined to Agricultural Extension Officers and the Ministry’s personnel. The owners use their smartphones, tablets or computers (that is, if they have any) to tap into the system to get information about their animals, they can communicate with extension officers and veterinaries about vaccines, sicknesses, water and grazing, as well as with private buyers and sellers. In addition, the absent cattle owners frequently use their mobile phones to communicate with their animals’ caretakers in order to stay informed about their herds. Thus, no doubt digital ICTs creep into the everyday life of people in Botswana.

“After all the changes have happened – historically speaking – in a split of a second.”

So why the ‘maybe not’? It might amount to being overly critical. After all the changes have happened – historically speaking – in a split of a second. A decade has gone since hardly anyone owned a mobile phone, most had not heard of the internet and communication was mostly from mouth to ear, or via radio and newspapers. Now Gaborone boasts of 4G networks, of mobile money and of WiFis everywhere. The problem is, however, that extensive use of internet is beyond the economic means of most Botswana. To take one relatively typical example:

Nyaga, a 23 yeas old single mother living in the capital, is among the relatively lucky few who have got a job. (The unemployment rate in Botswana is about 20%, and as high as 41,7% among young in the agegroup 15-24). She has Samsung smart phone and can in principle access internet anywhere , anytime. However, while Botswana came out with good scores in a recent report on internet in Africa, it was one area it scored badly – the consumer costs of using telephony and internet. Apart from the fact that the landscape of airtime packages from the service providers is extremely difficult to navigate in, the price level is generally high. Nyaga can’t afford browsing on Facebook the ways young people do it in Europe (the fact that Botswana has the highest percentage of Facebook users in mainland sub-Saharan Africa, does not say much about how much they use it). She has to save up for some intense, concentrated scrolling and postings and then she has to wait for some days before she can get online again. The only alternatives for a full-fledged use of internet are getting free access through your workplace or entering a WiFi-network that enables her to surf for free. The problem is, however, that it is mostly hotels, restaurants and cafes that have WiFi and they are almost without exception password protected. What she would gain in free surfing would be lost in having to buy some beverages to be allowed to use the network. Of course, those who have access to the internet through their workplaces can maximize that opportunity but Nyaga, as the vast majority of young people, are not that lucky.

Now, being regularly on Facebook can of course be considered a pastime luxury, without societal significance. However, the vast majority of youth we have conversed this far, Nyaga included, stress the importance of being connected: It is an important tool for maintaining networks – they represent social capital, which can be converted to important cultural and economic capital in the form of real jobs, smaller and larger opportunities for making money and not the least providing information that can mean the difference between a bright and a bleak future.

Thus, the wealth gulf that exists within Botswana also suggests a intra-national digital divide, a divide that easily increases the already worrisome divisions within the Botswana society. Furthermore, the opportunities that lies in the ICT revolution – which in this respect basically consist in enhancing the speed and smoothness of communication between people, thus enabling positive societal developments – is hampered by an unfortunate economic inequality, as well as what seems to an outsider to be an ICT service provider sector that can be characterized as an oligopoly. There are only three actors in the Botswana market (Mazkom, Orange and Be) and this seems to explain the weak competition and hence the high price for mobile telephony and internet use for the consumer.

This being said, the future is in no way bleak. The youth are, after all, on internet, and - even more importantly - they have a strong desire for being part of the global online community, acknowledging the importance internet has for their own and their country’s future.